How does your estimated lifetime tax bill compare historically?

Does history help you make a judgement whether the amount of taxes you pay is fair and reasonable?

Last but not least, once you understand the historical context, will it help you determine what your future tax bill is going to look like?

The following shouldn’t just be useful for your financial planning, but it’ll also give you a lot of morsels you can use to appear clever at cocktail parties.

A few figures your grandparents (and great-grandparents) would have been familiar with

Today, tax rates add up to somewhere between 30% and 70%. For most Western countries, it’s closer to the upper end of that span once you count all the hidden taxes (such as inflation).

Historically, such a high level of taxation is a relatively recent phenomenon. Until 1914, the overall tax burden on citizens was no more than 15%. Income tax rates were generally between 2% and 6%.

What changed?

World War I happened, which gave governments the world over the justification to implement sky-high emergency tax rates. In Britain until 1914, the then equivalent of income tax (the so-called “rates”) was limited to between 3.75% to 6%. By 1918, it had risen to a minimum of 30% and a maximum of over 50%.

Until 1914, the overall tax burden on citizens was no more than 15%. Income tax rates were generally between 2% and 6%.

The same happened in most other major European countries. The United States, on the other hand, managed to stick to its low tax rates, primarily because they remained on the sidelines for much of World War I.

After the war, taxes in Europe weren’t lowered, but governments found new justifications for collecting and spending the money. Also, as you’d expect after a proper war, there was a lot of debt that had to be serviced and paid off. The increased taxes had been sufficient for paying just 25% of the war’s overall costs, and Britain funded much of the rest through debt.

A short two decades later, the world entered the Second World War. Needless to say, that wasn’t a time to lower taxes, either. Countries that somehow had escaped the financial burden of World War I were inevitably caught up in World War II. Americans made acquaintance with the benignly named “Revenue Act of 1942”, which packed a punch. Up to that point, only 13 million Americans had to pay any personal taxes at all. From 1942 onwards, this number rose to 50 million. By 1944, the top rate for American taxpayers was a 94% tax. The Second World War cost the American taxpayers an estimated USD 3tr in today’s money.

Once again, the end of the war didn’t end higher taxation. Despite the much higher tax rates during the two world wars, most of the countries involved were only able to pay for some of the war from tax income. The US could only fund 48% of the war efforts through taxes, with the remainder coming from government debt. America’s debt-to-GDP ratio exploded and reached 110%. In case you are wondering what these figures mean, anything above 70% is generally considered financially unhealthy.

After the Second World War, governments used a range of justifications not to return their tax rates to the old level:

- Debt required paying off. Britain paid off the last of its World War I debt in 2015!

- The US fought several other major wars, which needed funding. Vietnam alone cost an estimated USD 500bn in today’s money.

- New “wars” were invented, including those that involved social goals rather than military objectives – such as the “war on poverty”, the “war on drugs”, and most recently the “war on terror”.

How did the governments’ modern-day warfare against presumed social ills fare?

War on poverty: By many measures, the Western industrialised world today has more financial inequality than at any time since the end of the Second World War. The West’s middle class is on the cusp of being wiped out, and the number of poor people is rising.

This OECD report highlights the plight of the Western middle class.

War on drugs: There are certainly more drugs available than ever before. In big cities, cocaine is about as widely used as aspirin. So abundant is its use that traces of cocaine are found in London’s drinking water supply.

War on terror: As Sadiq Khan, the Mayor of London, informed his citizenry: terrorism is “part and parcel of living in a big city“. Why am I not convinced that the war on terror has been overly successful?

So much for governments’ efforts to wage and win major “wars”. How well your tax money is spent is a question you may have asked yourself before.

If your great-grandparents were still around and could tell you about the pre-1914 era, they would undoubtedly be able to share some alternative views on the suitable, fair level of taxation.

Alas, they aren’t around anymore. In fairness, one also needs to say that some aspects of that era were either not comparable to today’s circumstances or would compare unfavourably.

So instead of dwelling on the past much longer, let’s take a look at the future. Your financial future, to be precise.

This article was inspired (and informed) by “Daylight Robbery”, Dominic Frisby’s seminal work on the history of taxation. I highly recommend you check out the book. Details at the end of this article, including an offer for a signed copy (UK only).

What are the 2020s likely going to bring for your taxes?

If you wanted to, it’d be easy to take an optimistic view of what’s to come.

Thanks to the coronavirus crisis, we were just able to witness governments creating trillions (!) of euros and dollars out of thin air (rather than increasing taxes). This proverbial helicopter money will be used to prevent companies from going under, and some of it will even be mailed to citizens as a cheque.

Proponents of the new, fashionable “Modern Monetary Theory” (MMT) will tell you there is no limit to governments issuing new money.

So, in theory, we should be able to stop paying taxes and instead have central banks create money from thin air. Everyone gets a cheque each month, called Universal Basic Income. And we all live happily ever after, right?

Not so fast. Anyone with a tiny dose of common sense will realise that someone will eventually have to foot the bill for this – someone, somewhere, someday.

Governments are masters at covering their tracks. For example:

- When the US introduced sky-high tax rates to fund the Second World War, it commissioned a Walt Disney film to sell the concept as “Victory Taxes”.

- The UK government invented “PAYE” tax (Pay As You Earn = deducted from your pay cheque) in 1943, and it was quite open about its aim to decrease taxpayers’ awareness of the amount of tax being collected.

- VAT is another highly effective way to obfuscate just how much money is collected. In countries where VAT is included in prices, shoppers don’t even realise what’s happening. In the UK, VAT makes up nearly a fifth of all government income. It is the second most significant source of governmental income (after income tax).

Today’s governments mainly rely on obfuscation, and that’s true the world over. The five programmes under which the US Federal Reserve Bank recently issued trillions of dollars are called CPFF, PMCCF, TALF, SMCCF, and MSBLP. How many citizens understand what’s going on? Probably 0.1% at best. For the other 99.9%, these are Spanish villages.

In the UK, VAT makes up nearly a fifth of all government income.

Where all this does eventually shine through is the level of overall debt these countries have to carry. We’ve already seen an explosion of government debt during the 2008/09 financial crisis. Still, the recent financial measures to deal with the fallout of the coronavirus crisis make 2008/09 look like child’s play in comparison.

As a result of the recent fiscal “stimulus”, Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio will jump by 33% to 167% of GDP. Portugal is going up to 146%, Greece is at 219% (red alert territory), Spain clocks 126%, and France follows at 123%. Remember, anything above 70% is considered dangerous territory. As an article on Investopedia explained:

“A study by the World Bank found that countries whose debt-to-GDP ratios exceeds 77% for prolonged periods, experience significant slowdowns in economic growth. Pointedly: every percentage point of debt above this level costs countries 1.7% in economic growth. This phenomenon is even more pronounced in emerging markets, where each additional percentage point of debt over 64%, annually slows growth by 2%.“

France has become a case study for the Western world’s addiction to ever-increasing government debt. The country has not had a single year with a fiscal surplus for over 40 years, and the French government eats up an eye-watering 57% of the country’s wealth generation.

Historically, high national debt is the surest precursor of high taxation. Higher debt always ends up with higher taxes or higher inflation – and quite often, both! These two are “unofficial taxes”.

Looking for clever ways to invest your hard-earned cash?

Head over to my investment website Undervalued-Shares.com for common sense investment opportunities from around the world. Ideas that you won't find anywhere else!

What if a second wave of bailouts became necessary as part of the overall coronavirus situation?

What if inflation had a revival and interest rates rose? Most governments have only been able to deal with the increased debt burden because interest rates have been so low. If they rose, the additional money required to service the debt would skyrocket. Given ultra-low interest rates, it doesn’t take much of an increase in interest rates to make governments face skyrocketing interest rate payments. If interest rates for Country A went from 2% to 4%, that’d be a 100% increase in interest expenses.

Throw in exploding costs for pensions and healthcare in most of the Western world, due to the collapsed demographics, general mismanagement, and the wilful operation of Ponzi schemes (such as pension schemes that aren’t built on reserves). There are ever more old people to take care of and pay a pension to. On the other hand, there are fewer productive and more unproductive young people. Did you know there are already specialised consultancy firms that help governments and companies to “minimise” (= wiggle out of) their pension obligations?

If you looked at such critical long-term trends and the orders of magnitude involved, does it sound like a winning combination to you?

Someone will have to pay the bill. Higher taxes for much of the Western world are probably a given for the upcoming decade.

Notice how the coronavirus crisis fast became the “war on corona”. It’s all you need to know to assess your future tax burden.

But it gets even worse than that. Let’s speak about the cost of complying with your government’s rules and regulations.

Your tax burden isn’t limited to the money you pay

Complying with taxes will also eat into your income, and a mere human error could even land you in jail.

This situation is due to the Western world’s bloated bureaucracies. Governments haven’t just unlearned how to live within their means, they have also expanded their bureaucracies beyond what is operationally required and financially sustainable. One of the truisms of bureaucracies, be they government or private sector, is that if left to their own devices, they will grow bigger, bolder, and less manageable over time. It’s the adage that “Work expands so as to fill the time available for completion“, which originated by Cyril Northcote Parkinson as the first sentence of an essay he published in The Economist in 1955. He based his finding on his extensive experience in the UK Civil Service, where he found bureaucracy growing at 5% to 7% p.a. “irrespective of any variation in the amount of work (if any) to be done.” Parkinson partly attributed this growth to officials wanting to increase their subordinates and to staff members making work for each other.

You may have come across the seven rules of bureaucracy:

Rule #1: Maintain the problem at all costs! The problem is the basis of power, perks, privileges, and security.

Rule #2: Use crisis and perceived crisis to increase your power and control.

Rule #3: If there are not enough crises, manufacture them.

Rule #4: Control the flow and release of information while feigning openness.

Rule #5: Maximize public relations exposure by creating a cover story that appeals to the universal need to help people.

Rule #6: Create vested support groups by distributing concentrated benefits and/or entitlements to these special interests, while distributing the costs broadly to one’s political opponents.

Rule #7: Demonize the truth tellers.

(You can read more about it on the Mises Institute website: “The seven rules of bureaucracy“.)

During normal times, bureaucracies only ever grow. They never shrink, unless something catastrophic happens.

To keep its bureaucrats busy (and its population under control), the UK government has created a tax code that now runs to 10 million words and 21,000 pages. That’s 12 times the length of the Bible.

Imagine how much time and effort is spent on complying with all these rules and regulations:

- Citizens have to find their way through this spaghetti code. They can either waste their own time or hire a tax advisor. The fees paid to the tax advisor are, de facto, nothing but another (hidden) income tax.

- Hordes of bureaucrats need to be employed and paid to administer the system. Your tax money should go to worthy causes, but instead, an outsize portion of it goes towards maintaining an excessive, self-serving administrative apparatus. A famous example in literature is that of the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK. Between 1997 and 2008, the number of hospital beds decreased by 30%, but the number of “managers” doubled!

- Decision-makers in government are forever wasting their time on tax-related questions instead of solving pressing issues. No wonder the papers are full of articles about problems that already existed decades ago and which have not fundamentally changed despite trillions thrown at them.

For the US, there is an annually updated estimate of the nation’s costs for complying with the tax code. It comes out at USD 400bn, which equates to about USD 1,500 for each and every American citizen. Complying with tax-filing requirements costs the US economy 8.9bn man-hours per year, which is the equivalent of 4.3 million people spending their time on nothing but doing tax returns. That’s the same number of people that are working as drivers in the US.

Complying with tax-filing requirements costs the US economy 8.9bn man-hours per year, which is the equivalent of 4.3 million people spending their time on nothing but doing tax returns.

I tried to find an estimate of the UK’s costs for complying with the tax code. The most useful document my search produced was a waffly parliamentary report dating back to 2003/04: “The Administrative Costs of Tax Compliance“.

Here are just some of the highlights of its conclusions:

“In the absence of firm data, it is not possible to determine conclusively how the administrative costs of tax compliance have changed over time.“

“Witnesses agreed that employer (or payroll) taxes generate the highest compliance costs for business and that these can fall disproportionately on small businesses.“

“Although measuring the administrative costs of tax compliance is difficult, comparative analyses confirm that the UK has lower administrative costs and fewer regulations than most EU countries.“

Needless to say, the report concluded that “it is an appropriate time to establish a deliberate strategy for reducing or, at least, containing tax gathering and benefit paying compliance costs.“

Equally needless to say, nothing much has changed since then.

If you fancy going down that rabbit hole, download the annual report of Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs for factoids that are both telling and amusing. The report loudly proclaims that it only costs GBP 0.0052 to collect each GBP 1 of tax. It’s not technically incorrect, but misleading. The figure only includes HMRC’s annual operating costs (salaries, offices, etc), not any other costs caused by the tax system. It does make for good PR soundbites, though. Refer back to rules #4 and #5 as per above.

As if! (HRMC annual report 18/19)

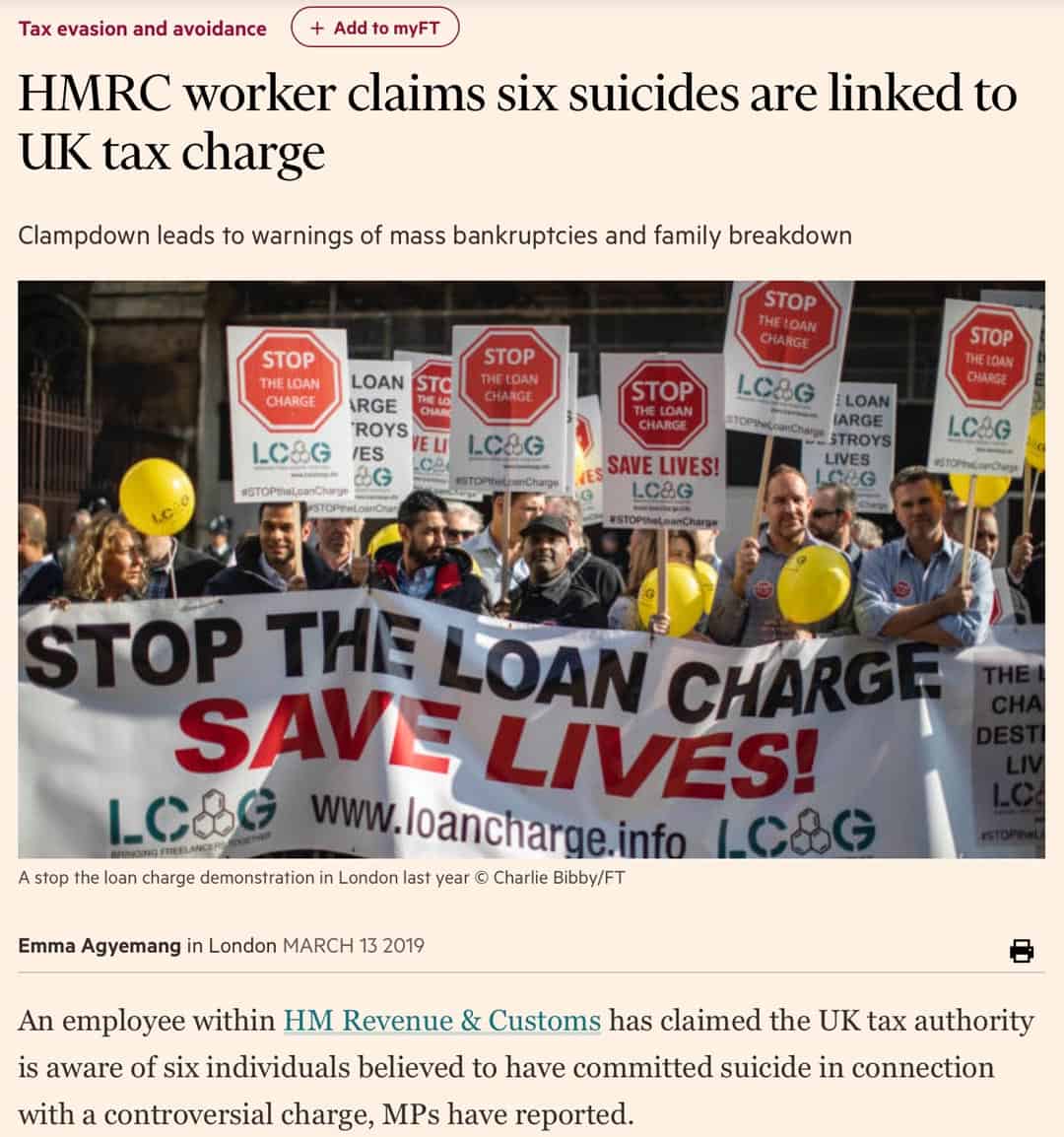

People who will not laugh about this (anymore), are those the UK tax code pushes into suicide each year. The lack of clarity and the sheer complexity of the UK tax code recently led to tens of thousands of contractors facing an additional tax bill for matters that go back up to 20 years. Many of them had filed their taxes based on the advice they had received from accountants. These were ordinary people running a small business and wanting to do the right thing. HMRC recently decided to prosecute 50,000 such cases, which the Financial Times reported was going to lead to “mass bankruptcies and family breakdown“.

Taxes can bring deadly complications, as the Financial Times reported in March 2019.

Six Britons are already confirmed to have committed suicide over the matter, and there are probably more who didn’t make it into the statistic. These cases relate to just one aspect of the tax code. It’s a code that no human being can understand or fully comply with. Stories like these used to involve wealthy people, but they now run wild among entirely ordinary taxpayers and small business owners. I am sure each and every one of these people would have previously thought that something like this could never happen to them.

Will the existing system ever change? I doubt it.

When George Osbourne became Chancellor (Finance Minister) of the UK in 2010, he promised a radical simplification. In his words, the UK tax code was “one of the worst and most opaque on earth“. He then set up the Office of Tax Simplification. The result? During his six-year tenure, the UK tax code doubled yet again.

Does it need to be like that?

Some countries will beg to disagree.

This country has the world’s shortest tax code (almost)

History and a look at countries around the world can provide a refreshingly different perspective.

There is an interesting rule of thumb how the world ended up divided into countries with higher taxes and lower taxes: those countries that didn’t participate in the Second World War tend to have much lower income tax rates. It’s not a perfect rule of thumb, but it is accurate in most cases. Among the OECD countries that have the lowest levels of government spending are Chile, Ireland, Costa Rica, and Switzerland. Their involvement in the Second World War was significantly smaller than that of the countries with the highest levels of government spending: Finland, France, Denmark, Belgium, and Greece.

Even today, there is a surprising number of countries that manage perfectly well without charging their citizens more than what would have been the standard level of taxation before 1914. A wonderfully measurable and relatable example is Hong Kong.

To this day, the tax code of Hong Kong only runs to 276 pages. Any citizen can read and understand it, not the least because some parts of it won’t apply to them.

Hong Kong’s economy was on a third world level after the Second World War. Today, its GDP per capita is 15% higher than that of the UK. The country has lifted its citizens out of poverty and provided an increasingly good quality of life to millions of new residents. It does have its issues, such as limited and overly expensive housing stock partly due to its tiny landmass. But its infrastructure and governmental services compete with the Western world in most regards and even outperform it in some respects. Pearson ranks Hong Kong’s education system as the fourth best in the world, and Bloomberg ranked Hong Kong near the top of the global healthcare index. The territory’s public transport system is generally viewed as the world’s best, thanks to its 99.9% “on-time success rate”.

A convoluted tax code is not a requirement for a thriving economy? Who’d have thought?

To this day, the tax code of Hong Kong only runs to 276 pages. Any citizen can read and understand it, not the least because some parts of it won’t apply to them.

Another useful example is Russia. For all its faults, the country reformed its income tax code in 2001. Everyone now pays a uniform income tax rate of just 13%. Russia has one of the world’s lowest debt-to-GDP ratios (20%), and it sits atop one of the biggest national cash reserves (USD 600bn). The country’s situation was aided by the fact that it sits atop massive natural resources. On the other hand, Venezuela owns the world’s largest oil reserve, yet it is drowning in debt and hyperinflation. The Russians do deserve credit for the fiscal policies of the past 20 years since Putin came to power. When it had to fund emergency measures to deal with the coronavirus crisis, it could afford to simply take a few billion out of its reserves. It’s called a fund for rainy days, and every country should aspire to have one, instead of running up ever-increasing amounts of debt that put the burden on future generations.

These are just some examples, and there are many more.

So, what do we make of all that?

Do you want to accept your financial fate?

By now, you should have realised that:

- You live in a period of extraordinarily high tax rates.

- Your government probably has an unfairly complex tax system.

- You could get caught up in complications that can diminish your savings, bankrupt you, have you thrown in jail, or even end your life.

- Looking out to the 2020s, it’ll probably only get worse.

The practical implications of all this are grave once you look at them from a lifetime perspective. Submitting to this system may not require you to have fewer pints in the pub tonight, but it will likely tack on many years to the time before you can afford to retire. You may not be able to retire at all and instead have to work till you drop dead (or until they switch off your life support in a hospital because you are already above a certain age and your country’s healthcare system is bankrupt). The word “death panel” will creep into day-to-day language over the coming years. Look it up if you haven’t come across it yet.

Which begs the question, what to do?

From a Western European or North American perspective, it’s often difficult to comprehend that there are a lot of countries that are handling their financial affairs in a way that is more beneficial for its citizens.

You don’t need to look as far away as Hong Kong to find alternatives. Even within Western Europe and North America (!), some loopholes and exceptions enable you to break free from this entire system. Legally, relatively easily, and even if you only have the income of a well-earning professional or a small business owner.

You could even ask the question: can you afford NOT to break free from this system? How will your financial health look like in ten or twenty years if you stay within your current tax system?

Here is a suggestion for a quick and effective way to answer this question for yourself.

The 10-second check if your taxes are acceptable or too high

You may still say: “Yes, Swen, but….“

The question of what is a reasonable, effective level of taxation generates a lot of controversies.

Person A will say that a high level of taxation has enabled the Western world to build its healthcare system and create a support net for those who have fallen on hard times. They’d consider any other way gravely immoral.

Can you afford NOT to break free from this system?

Person B will say that the West’s healthcare system is in decline and that the support system only leads to ever more people relying on handouts. An excessive welfare system, in turn, can only be paid through raising ever more debt and burdening future generations. They will consider the current system gravely immoral, too.

You could spend the rest of your life fighting out this argument. I have decided there are better things to spend my time on. Always keep in mind that your time on this planet is limited. Memento mori!

The good news is, there is a shortcut for you to make a decision.

I’ve spoken about this subject with many taxpayers over the years, and thus believe there is a magic threshold that governments should respect:

- Up to 20% total taxation (including hidden taxes), very few people would ever complain or make an effort not to pay.

- If tax rates are between 20% and 30%, some (but not all) people will start to go to great lengths to avoid (legally) and evade (illegally) taxes.

- Above 30%, a large number of people will feel they are taxed unfairly.

There is a sufficient number of well-run countries around the world that operate a stable and thriving society on the back of no more than 20% taxation.

Or as I always say: “I am happy to work for the government on Mondays, because we do need roads, policemen and courts. From Tuesday to Friday, it has to be for myself. And if I work on weekends, it sure as hell has to be for myself.“

Based on your view of the world, nothing speaks against you creating your own threshold. You might have reasons and convictions that make you believe that 35% is the right rate – each to their own. Just make sure you are not missing out on counting the hidden taxes about which you have now learned so much more. Also, don’t forget to do some rough calculations how your life will look like in a few decades, once you cannot actively work anymore.

Based on your conclusion, you should make a decision for or against staying in the system that you are currently in.

In part 3 of my Understanding your “lifetime tax bill” series, I will show you some alternatives that you could use to make a lasting, positive change for your finances.

A special thank you and book recommendation: I could not have written this article without the seminal work done by Dominic Frisby. His 2019 book “Daylight Robbery – How Tax Shaped Our Past and Will Change Our Future” is the single best book available on the topic, and many factoids in this article are lifted straight out of his book. It’s wonderfully enjoyable and entertaining (e.g. you’ll learn why surnames only exist because of taxation and how ancient Greece managed to keep taxes voluntary), and helps you shape your financial planning. The book is also available as audio book, and Dominic operates his own YouTube channel. If you would like a signed copy (free UK delivery), please contact him through his website.

If you liked this article, you will probably also enjoy:

Want to print this article? Open a printer friendly version.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: